William Friedkin’s Top10

“I discovered Criterion in the late eighties with the laserdisc of Citizen Kane, which I still watch,” writes director William Friedkin, whose films include The French Connection, The Exorcist, Sorcerer, and 2011’s Killer Joe. “Since switching to DVD and Blu-ray, I’ve acquired at least a hundred of your titles and don’t dare look at your complete list or I’d want them all, leaving me no time for anything else. Five of the films on this list are French and another is about France. One is from Japan, one is Danish, one is from England and one is from the U.S. Six (and a half) are in black and white. None were made later than 1979. I could easily have chosen scores of others from different countries and years. That is the power and range of the Criterion Collection, whose films occupy entire bookshelves in my home. Here are some of the ones I continue to watch—in no particular order.”

-

1

Charles Laughton

The Night of the Hunter

I was twenty years old when I first saw it. It terrified me then, and still does. The preacher, played by Robert Mitchum, is the most frightening psychopath I’ve ever seen depicted. This is the only film directed by Charles Laughton, and its haunting, over-the-top storytelling is reminiscent of Laughton’s own character portrayals. The poetic, expressionistic images are by Stanley Cortez, a true American master who I fortunately came to know many years before his death. Stanley photographed, among others, The Magnificent Ambersons and The Three Faces of Eve, in which his lighting is equally unique. The disturbing orchestral score is by Walter Schumann, who also wrote the Dragnet theme and whose music underlines and drives the horror the way Bernard Herrmann’s does in Psycho. This is one of James Agee’s rare screenplays—another was The African Queen—and it captures America in the Depression as well as did his book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, with photographs by Walker Evans. The film’s story is an American equivalent of the Brothers Grimm.

-

2

Alain Resnais

Night and Fog

An early work by Resnais. It’s only a half hour long, but I’ve not seen a film of any length that matches it in emotional resonance. It transcends the documentary form. I saw it around the time I first saw The Night of the Hunter, in the late fifties, and I was about to film my first documentary. Night and Fog begins with a beautiful color landscape beneath a blue sky. The camera cranes down to reveal a long stretch of barbed wire, followed by shots of vast fields overgrown with tall grass, trees, and wildflowers. The camera tracks slowly across the placid landscape, dotted with abandoned red brick buildings that could have been warehouses or barns; then a sudden shock cut to black-and-white footage of victims of the Holocaust. The long, tracking color shots of the killing fields of Auschwitz and Majdanek, only ten years after the end of the Second World War, are intercut with horrific black-and-white shots of piles of dead bodies, rooms filled with women’s hair, and personal effects. A dry, dispassionate narration is heard throughout, written by Jean Cayrol, a survivor of the camps. Night and Fog is one of Resnais’ first “memory” films and points the way to his later masterpieces, Hiroshima mon amour and . . .

-

3

Alain Resnais

Last Year at Marienbad

This one really shook up the filmmakers of my generation before we started making our own films. The late comedian Bert Lahr told me that, when he was in the first production of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot in 1956, “I did that damn play for ten weeks, and I never understood a word of it.” I’ve seen Marienbad at least twenty times over the past fifty years, and I don’t understand one scene of it, but what a fantastic experience. I don’t understand the Grand Canyon or Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night, either, but they continue to move me. Marienbad is that rare film that changes the possibilities of narrative in cinema. I no longer try to “figure it out”; I just let it take me. The soundtrack can get on my nerves, but the film itself is visual music.

-

4

Henri-Georges Clouzot

Diabolique

Ranks with the best of Hitchcock, who wanted to make it but Clouzot beat him to the rights. It was made in the same year as Night and Fog and The Night of the Hunter, 1955—what a year, what a decade for world cinema. The penultimate scene had the same effect on me as Psycho. Though it no longer holds surprises for me, I watch it for its mastery of suspense and the performances of Paul Meurisse, Simone Signoret, and Véra Clouzot. But I confess that the nine-minute scene without words where Véra hears noises from her bedroom, goes down the hall to check them out, and is literally scared to death still nails me. You can bet I thought about how it was shot and paced when I sent Ellen Burstyn up to that attic in The Exorcist. No nudity, no sexuality, no violence, just pure, slow-building suspense that escalates to terror. The original novel was written by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, who also wrote Vertigo.

-

5

Carl Th. Dreyer

Ordet

Directed by the Danish master Carl Theodor Dreyer, Ordet is yet another film made in 1955 to which I’m deeply indebted. There is a stunning scene of literal resurrection that inspired my own visual approach to The Exorcist and gave me the courage to stage a supernatural event as if it were actually happening, without scary lighting or weird angles. Like many of Dreyer’s other films, including Vampyr and The Passion of Joan of Arc, Ordet is based on literary source material (in this case, a play). But all his films are deeply spiritual in their examinations of the mystery of faith, and purely cinematic.

-

6

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

The Red Shoes

Freely adapted from a story by Hans Christian Andersen. It’s a must for anyone interested in the art of film. It always seems to me a work of true madness about a descent into madness. Original and timeless, it’s also a glorious celebration of classical ballet and the pain and effort it takes to make it. The matchless beauty of Moira Shearer is captured by the cinematography of Jack Cardiff, and Anton Walbrook (as the impresario of the ballet company) gives an unforgettable performance, one that alone is worth the price of admission. The film is a transcendent experience, and the Criterion Blu-ray gives new luster to the imagery and sound. You need to see this, unless, like me, you’ve already watched it endlessly.

-

7

Stanley Kubrick

Paths of Glory

If 1956’s The Killing set the scene for a visionary new director, Paths of Glory, released a year later confirms it. Adapted from a novel that had appeared two decades earlier, the film has gained stature over the years. It is the darkest evocation of war ever filmed; you feel the pain, the fear and discomfort experienced by French soldiers engaged in a meaningless, suicidal battle with a faceless German enemy. The cast of American actors convincingly portray heartless French officers and outnumbered enlisted men. Kirk Douglas gives his best performance as Colonel Dax, as does Adolphe Menjou as Dax’s antagonist, General Broulard. You can see Kubrick’s early influences, Orson Welles and Max Ophüls, in his camerawork and editing style, but the film is totally original and powerful, and even has a touch of sentimentality in the final sequence. The famous tracking shots in the trenches accompanied by the constant drumbeat of bombs and artillery will remain in your memory long after you’ve experienced the film. The contrast between the high-living generals and the downtrodden soldiers is also a constant reminder of the folly and inequity of war.

-

8

Jean-Pierre Melville

Le samouraï

The ultimate existential gangster film. Hypnotic, detailed, ritualistic, it has influenced films like John Woo’s The Killer and the more recent Drive. Alain Delon gives his most memorable performance as an ice-cold assassin above such mundane concerns as moral conscience. Though violent in its subject matter, Jean-Pierre Melville’s film is also cool, meticulously lit, and classically framed. It operates in a kind of dream state. It’s the opposite of the fevered emotional style of most gangster films. The pauses and silences help make it the visual equivalent of Harold Pinter’s dialogue. This is my favorite Melville film, and the extras are among Criterion’s finest, including an interview with John Woo and one with Melville himself.

-

9

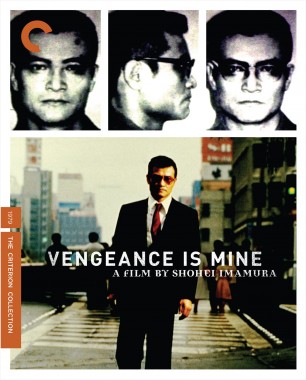

Shohei Imamura

Vengeance Is Mine

A tough, energetic chase film from Japan in the late seventies, based on a true story, with a strong performance by Ken Ogata as an outwardly charming con man and serial killer. It differs from the formal style of the great Japanese filmmakers like Ozu, to whom Imamura was an assistant. When Imamura started directing, he wanted to make films as unlike Ozu’s as possible, and Vengeance Is Mine is the best example of that. He leaves all judgment of his characters to the viewer, and the film is both operatic and contemporary. Beautifully photographed, it’s at times surreal and at other times plays like a documentary, which some viewers have found confusing, especially Imamura’s fracturing of the timeline. Those who love film and know Imamura’s others, like The Eel and The Battle of Nayarama, will find this one essential.

-

10

Luis Buñuel

Belle de jour

A thriller wrapped inside an enigma, this is my desert island disc, the one I’ve watched more than any other on this list. The psychology of the characters is revealed slowly and ambiguously. Each time I see the wheelchair (the husband’s fantasy) and hear the sound of the horse-and-carriage bells (the wife’s), and the way the two achieve harmony in the final scene, I’m reminded of Luis Buñuel’s ability to fuse reality and illusion in his characters and for the viewer. He performs this magic in plain view, like the best magicians. This is the film that illustrates that Catherine Deneuve is not only one of the world’s most beautiful women but a fine actress. Belle de jour is truly subversive in its satiric depiction of middle- class society, the church, and our social mores. If a ratings board ever understood this film, it would receive an NC-17, though there is no sex and little violence.