War and Peace: Saint Petersburg Fiddles, Moscow Burns

In July 1998, while attending the Moscow International Film Festival, I was shown around the cavernous lot of Mosfilm, the official studio through which the bulk of Soviet cinema was filtered. Unlike the festival, which was finding its capitalist feet with a blast of Hollywood-style glitz, Mosfilm was a ghost town. As my host, the studio’s newly appointed head, Karen Shakhnazarov, explained sadly, less than a decade after the fall of the Soviet Union, state funding for films had all but collapsed. He told me that the studio’s output had shrunk from a robust four hundred films a year in the eighties—when government money was still pouring into approved artistic projects, as it had been since Nikita Khrushchev’s post-Stalinist thaw of the early sixties—to a paltry four.

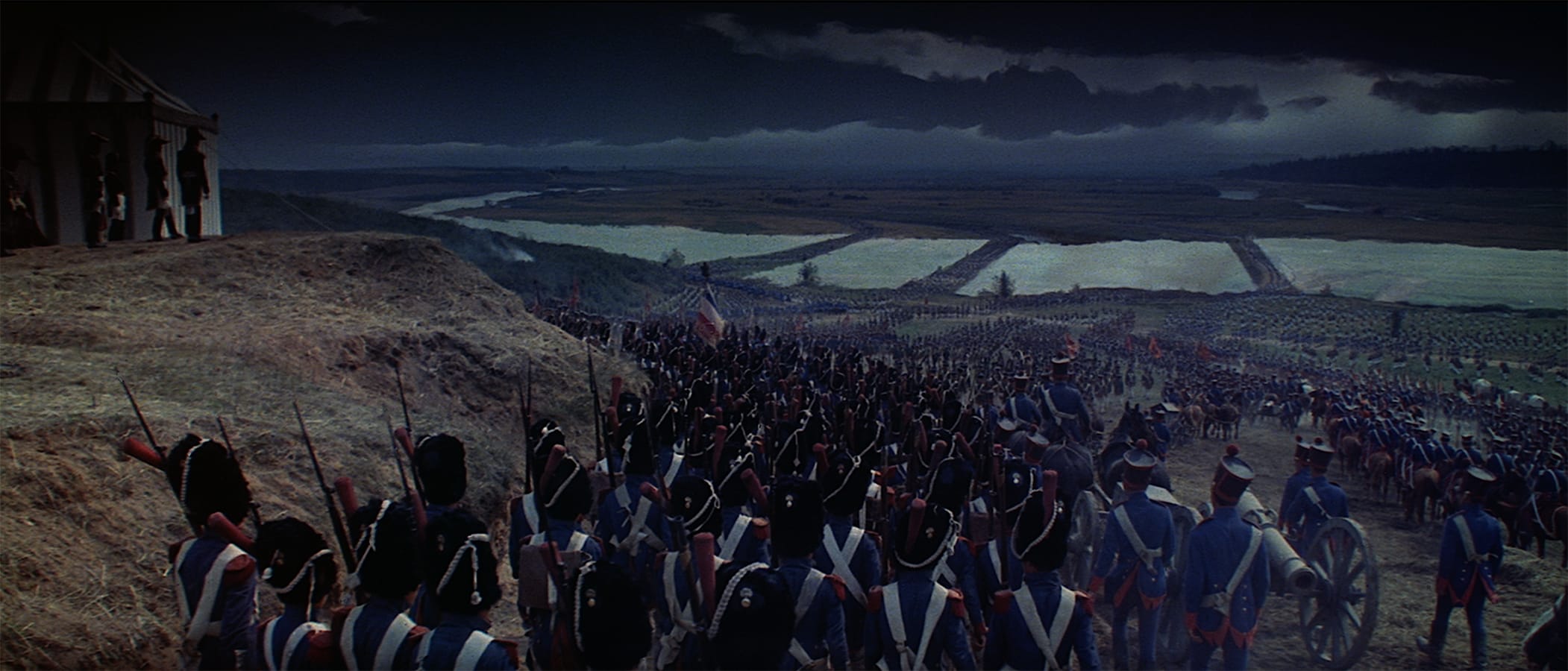

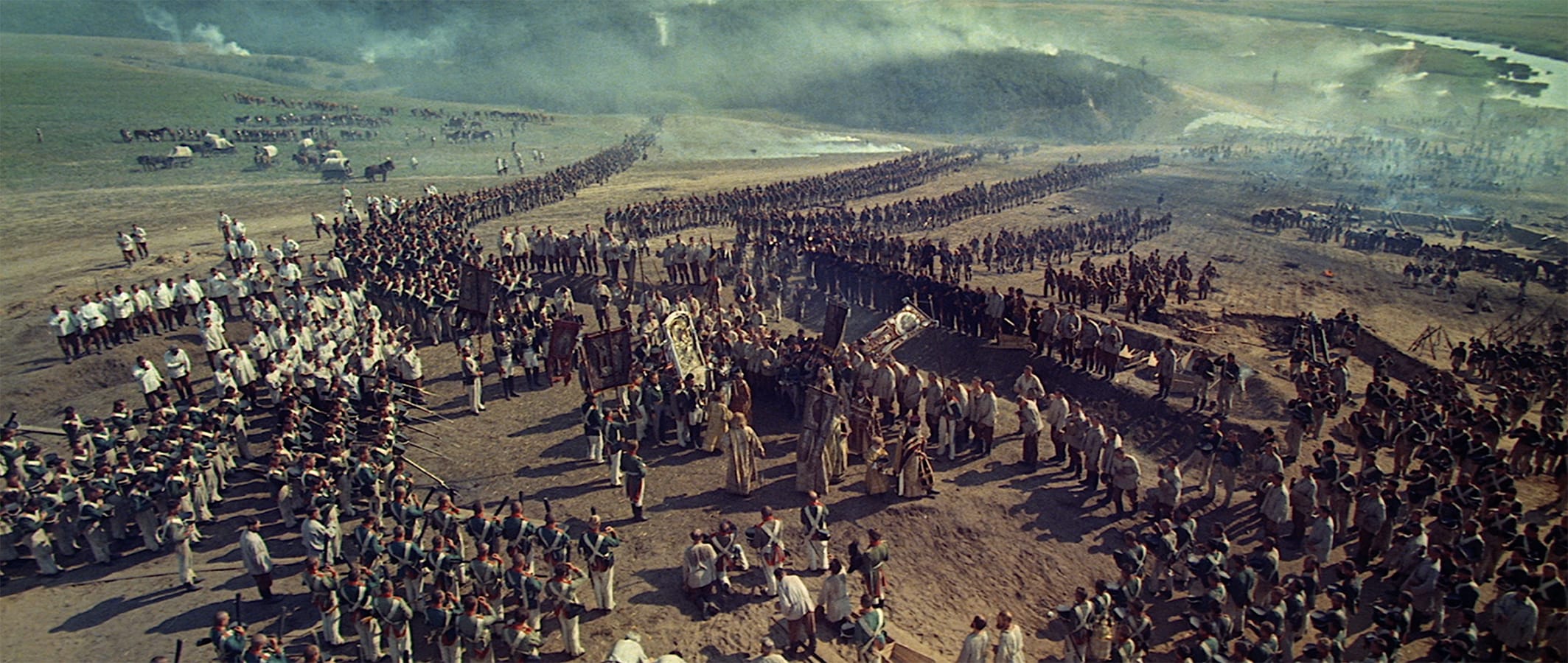

One notable recipient of the Kremlin’s lavishness during the studio’s glory days was an ambitious adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, released in four parts in 1966 and ’67 and directed by Sergei Bondarchuk, a young Turk who had made only one other film, a 1959 adaptation of Mikhail Sholokhov’s short story “The Fate of a Man.” Extravagantly resourced and shot in 70 mm, this eight-hour epic was planned to mark the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino, a major event in Tolstoy’s novel.

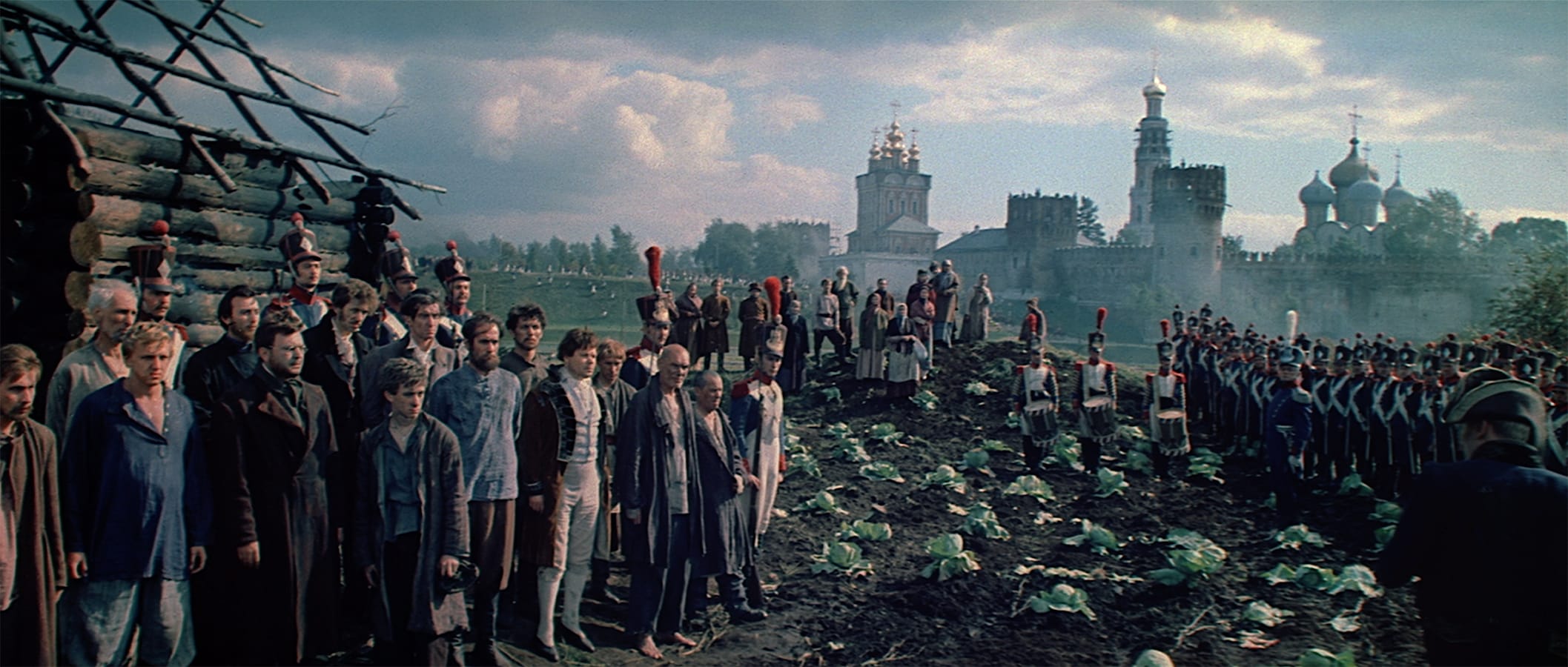

It was also hoped that Bondarchuk’s version would represent a Cold War cultural victory over the United States by outshining King Vidor’s 1956 War and Peace, a splashy Hollywood release starring Audrey Hepburn as Natasha Rostova and a quaintly miscast Henry Fonda as the portly, decidedly unheroic key figure, Pierre Bezukhov. A box-office flop in the U.S., Vidor’s film had played to large audiences in the Soviet Union. Newcomer though he was, and with a penchant for bold experimentation, Bondarchuk was also the kind of traditional Russian nationalist the Soviet leadership was looking for to upstage Vidor. “Why is it that this novel, the pride of Russian national character, was adapted in America?” Bondarchuk wrote to friends in 1961. “It’s a disgrace to the entire world!” Released to audiences at home in four parts, his War and Peace doesn’t lack for Soviet-style nationalism. As far as state-sponsored prestige pictures go, though, it’s a magnificent specimen of the breed, and one that keeps imaginative faith with Tolstoy’s evolving humanism and ecstatic spiritual inquiry.

I saw War and Peace for the first time in 1970, in a drafty movie theater during a year’s sojourn in Scotland, where, as a freshly minted university graduate, I was working at a job that didn’t come close to filling my days or my mind. Hooked on the melodrama of all things Russian, I had just filled a cold, wet Glasgow winter reading Tolstoy’s massive 1869 opus. So I was delighted when my boyfriend came home waving tickets to the Soviet War and Peace. We must have seen the butchered version of Bondarchuk’s film, hideously dubbed and cut for Western audiences. But to this child of a quiet London suburb where (so I thought) nothing ever happened, a film that asked, “How shall we live?” and answered on the broadest, deepest of canvases came as the antidote to my post-university ennui and indirection. Bondarchuk’s War and Peace offered glitzy balls and epic battles; a love triangle, albeit one more dreamy than steamy; a two-family saga that flayed imperial Russia’s heedless superrich while redeeming several of its spoiled scions; spiritual agony and ecstasy by the gallon resolving into equanimity.

Since my visit to Moscow, Mosfilm, though still state-owned, has rebounded with funding from commercial venues and other ventures, such as film festivals and YouTube releases of classics from before and during the Soviet era. Among them, after a slew of inferior resurrections, is a proud new War and Peace, restored at full length in 2K resolution and with the endorsement of Russian president Vladimir Putin, who wants (according to Denise J. Youngblood, author of the lively book Bondarchuk’s “War and Peace”: Literary Classic to Soviet Cinematic Epic) to “restore a proper patriotic culture” to the motherland.

Tolstoy wrote his sprawling novel, set during and just after the Napoleonic Wars but inspired by the Decembrist uprising of 1825, in six years. Bondarchuk took nearly as long to make the film, meanwhile suffering two heart attacks, one of which (reportedly experienced while watching Mikhail Kalatozov’s 1964 I Am Cuba) almost killed him. No wonder: adapting War and Peace for the screen presents enormous challenges, and the director also plays the central character, Pierre Bezukhov, whose odyssey from unhappy wastrel to moral and philosophical seer drew heavily on Tolstoy’s own evolution from womanizing gambler to enlightened social reformer and champion of Russians outside his own aristocratic class.

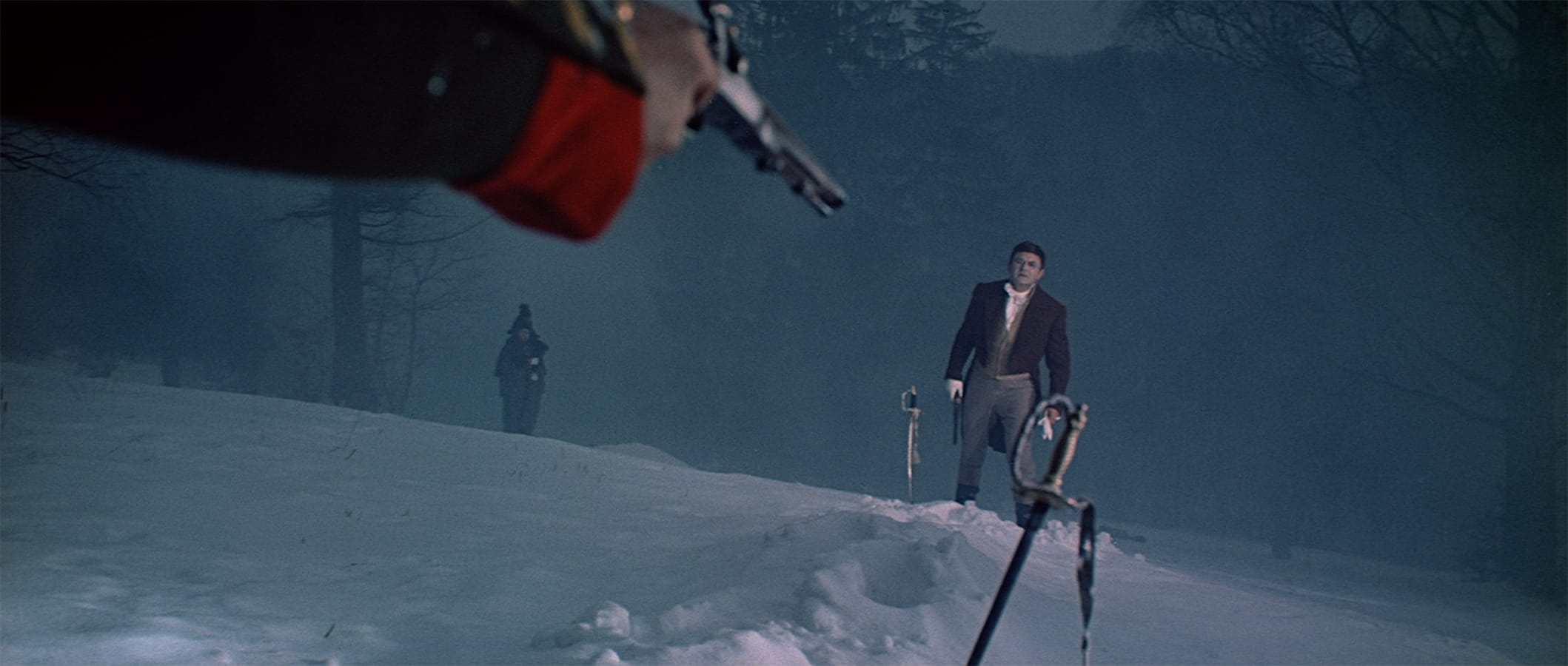

The difficulty of this particular adaptation arises not just from the dilemma of how to find a visual language for the inner crises that plague the trio at the novel’s heart—Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, Pierre Bezukhov, and Natasha Rostova. The novel’s length, its multitude of characters (the film has three hundred speaking parts), its mushrooming subplots and digressions into philosophy, politics, and religion, famously moved Henry James to dismiss it as a “large loose baggy monster.” That it is—as well as a flawed masterpiece that both emulated and broke with the structural forms of the nineteenth-century Western novel. Like Charles Dickens, whom he read avidly, Tolstoy was a precise and intimate observer of the physical and psychological details that reveal the essence of character. His battle scenes lend themselves readily to an epic war movie, and Bondarchuk made one with enough creative flair to echo the novelist’s bold venturing across genre lines, as he oscillates between the public and the domestic.

“For Bondarchuk, landscape and weather offered a mercurial register—foreboding, ecstatic, terrifying—of Tolstoy’s inner and outer shifts.”

“One can only marvel at the technical virtuosity of the special effects, mounted with aerial and crane shots, split screens, dissolves, and slow pans across hundreds of corpses strewn bent and twisted on the battlefield.”